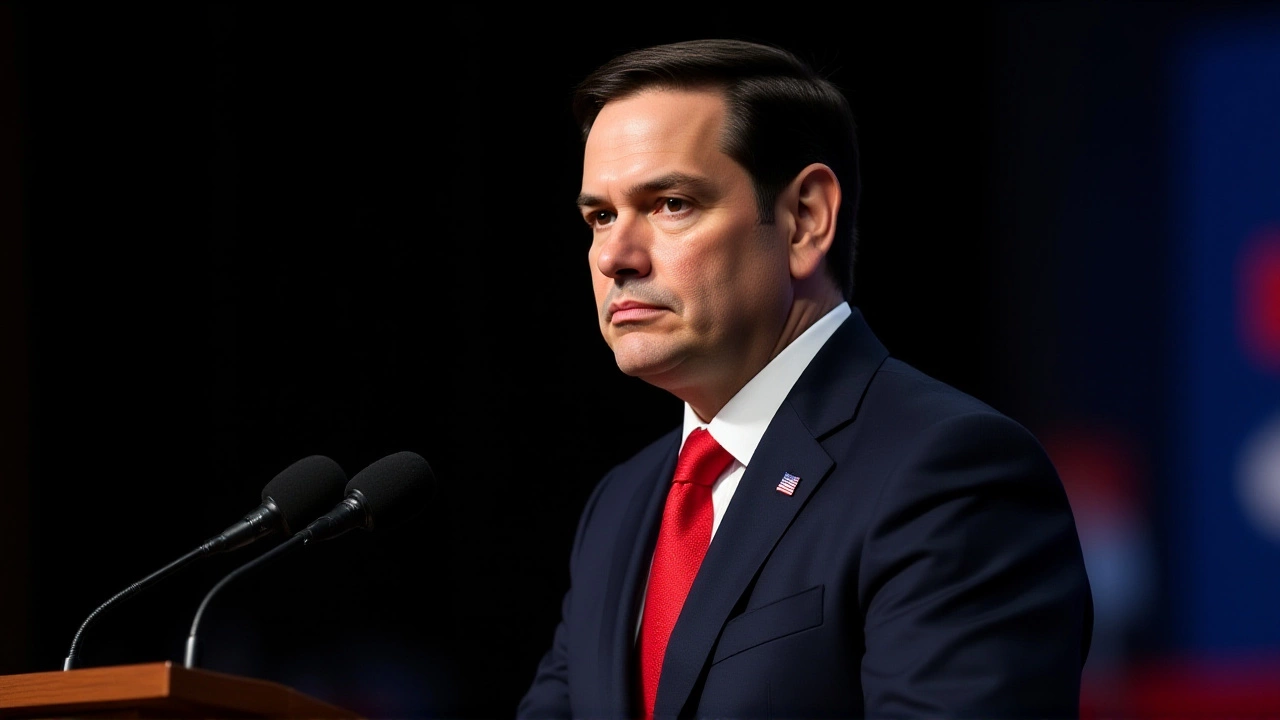

Rubio Secures Deportation Deal with Bukele Amid China Warning at Panama Canal

When Marco Rubio landed in San Salvador on February 4, 2025, he didn’t just bring diplomatic talking points—he brought a deal that could reshape how the U.S. handles migration: Nayib Bukele, El Salvador’s president, had just agreed to accept deportees of any nationality, including American citizens. It was an offer so startling, even seasoned State Department insiders paused. And it came on the heels of Rubio’s blunt ultimatum to Panama: remove China’s influence from the Panama Canal, or the U.S. would. The timing wasn’t accidental. Between February 1 and 6, 2025, Rubio visited five nations—Panama, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic—on what the State Department called a "strategic migration and security tour." But behind the official language was raw urgency: the U.S. was running out of options. On February 3, just hours before confronting Panama’s foreign minister, Rubio watched a U.S.-funded deportation flight lift off from Panama City, carrying 43 migrants bound for Colombia. It was the third such flight in 72 hours. The U.S. had spent $2.3 million on these operations since January, according to internal State Department records. The goal? Deterrence through visibility. "We want people to see what happens," a senior official told reporters anonymously. "Not just in Texas. Here. In their own backyards." But the real headline wasn’t the flights—it was the agreement with Bukele. El Salvador, already under a state of emergency since March 2022, has arrested over 83,000 people with minimal due process. Prisons are overcrowded, water is scarce, and sanitation is nonexistent in many facilities. The State Department’s own 2024 human rights report called conditions "inhumane." And yet, Rubio didn’t blink. "We’re not here to judge their justice system," he said after signing the memorandum. "We’re here to stop the flow." The deal explicitly includes provisions for Venezuelan nationals convicted in the U.S. if Caracas refuses to take them back. That’s critical. Venezuela, which lacks a functioning passport system, has been on the U.S. travel ban list since June 2025, after the White House cited its "inability to cooperate on identity verification." But with over 12,000 Venezuelans detained in U.S. custody last year, someone had to take them. Bukele volunteered. The move drew immediate criticism from human rights groups. "This isn’t diplomacy—it’s outsourcing incarceration," said Human Rights Watch in a statement. "We’re sending people to a country where they’ll be locked up without lawyers, without trials, and without hope of appeal. That’s not a solution. It’s a moral collapse." Meanwhile, in Panama, Rubio’s warning about China was equally seismic. "If you don’t move immediately to eliminate China’s presence at the Panama Canal," he told Panamanian President José Raul Mulino, "the United States will act to do so." The remark wasn’t metaphorical. U.S. intelligence had flagged Chinese-backed infrastructure projects near the canal’s Pacific entrance, including a new logistics hub funded by a state-owned Chinese firm. The U.S. military had already rerouted two naval patrols away from the area, citing "operational risks." The message was clear: the canal isn’t just a trade route—it’s a strategic choke point. The trip also unfolded against a backdrop of chaos in Washington. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the government’s main foreign aid arm, had been frozen since January after Congress failed to pass a funding bill. Programs that once supported anti-gang initiatives in Central America were shuttered. "We’re replacing development with detention," said former USAID deputy administrator Elena Mora in an interview. "It’s cheaper in the short term. But it’s a dead end." Rubio’s team insists the strategy is working. Since the start of 2025, apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border have dropped 18% compared to the same period last year. The administration credits the new deportation agreements and expanded travel bans—which now target 12 countries, with rumors swirling about 43 more on the horizon. But experts warn the numbers may be misleading. Smugglers are rerouting migrants through Nicaragua and Belize, where border controls are weaker. And the humanitarian toll? That’s invisible in the statistics. In Guatemala, Rubio met with officials who quietly admitted they couldn’t handle even 10% of the deportees the U.S. might send. In the Dominican Republic, officials expressed interest in a similar deal—but only if the U.S. would fund their border patrols. Rubio left without signing anything. The most unsettling moment came in San Salvador. When asked if Bukele’s offer extended to American citizens, Rubio didn’t hesitate. "If an American commits a crime here, and they’re deported, and El Salvador takes them—that’s their sovereign choice. We’re not stopping them." The room fell silent. No one asked what would happen if an American citizen ended up in one of those prisons. This isn’t just about immigration anymore. It’s about power. It’s about who gets to decide where people go when they’re no longer welcome at home. And for the first time, a U.S. secretary of state didn’t just ask a country to help—he asked it to become America’s jailer.

Why El Salvador? The Calculus Behind the Deal

El Salvador’s willingness to accept deportees of any nationality isn’t altruism. It’s a calculated gamble. Bukele’s government has spent the last three years building a reputation as the toughest on crime in Latin America. By agreeing to take U.S. deportees—including those from countries that refuse them—he’s signaling to Washington: "I’m your most reliable partner. Reward me." In return, El Salvador has already secured $400 million in U.S. security assistance since 2023, including drones, armored vehicles, and training for its national police. The deportation deal could unlock billions more. For a country with a GDP of just $26 billion, that’s transformative. But the human cost is staggering. With over 83,000 people detained since 2022, El Salvador’s prison system is operating at 300% capacity. In the notorious CECOT facility, inmates sleep three to a cell meant for one. Medical care is nearly nonexistent. Families report being denied visitation for months. "They’re not just taking our criminals," said Ana Ruiz, whose brother was deported from Florida after a DUI conviction. "They’re taking anyone the U.S. doesn’t want. And no one’s asking if they’re guilty."The China Factor: More Than Just the Canal

Rubio’s warning to Panama wasn’t just about the canal’s physical infrastructure. It was about digital control. U.S. intelligence reports indicate that Chinese firms are installing surveillance systems at key canal transit points, including facial recognition cameras and AI-powered vessel tracking software. The data, officials fear, could be shared with Beijing’s military. The U.S. has long relied on the canal for rapid naval deployment between the Atlantic and Pacific. A single U.S. aircraft carrier takes 8–10 hours to transit. If China gained access to real-time movement data—or worse, influenced scheduling—it could cripple U.S. military response times. Panama’s government denies any military collaboration with China, insisting the projects are purely commercial. But the U.S. isn’t convinced. A senior Pentagon official told reporters, "We’ve seen this script before. First, they build a port. Then they ask for a 99-year lease. Then they station ships. We’re not waiting for the third step."

What’s Next? The Domino Effect

Rubio’s trip has already triggered ripple effects. Colombia, which received the 43 migrants from Panama, is now lobbying the U.S. to take them back. Mexico is quietly expanding its detention centers. Honduras, which has yet to sign any agreement, is reportedly preparing a counteroffer: "We’ll accept deportees if you fund our schools." The Trump administration is reportedly drafting an executive order to formally designate El Salvador as a "safe third country" for all deportees—a move that would bypass Congress. If passed, it could set a precedent for similar deals with other nations. Meanwhile, the State Department’s internal memo on the trip ends with a single line: "We solved a problem today. But we created a new one tomorrow."

Background: The Rise of the Deportation Diplomacy Era

This isn’t the first time the U.S. has outsourced its immigration enforcement. In 2019, the Trump administration tried a similar deal with Guatemala. It collapsed after courts ruled the country wasn’t safe for asylum seekers. In 2021, Biden paused deportations to El Salvador after a judge cited its state of emergency. But today’s political climate is different. With the 2026 midterms looming, the White House is under pressure to show results. And Bukele? He’s become the model: authoritarian, effective, and unbothered by international criticism. The real question isn’t whether this deal will work. It’s whether the U.S. is willing to live with the consequences.Frequently Asked Questions

How does this affect migrants from Venezuela and other countries without diplomatic ties to the U.S.?

Migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, and other nations with no functional embassies in Washington now face indefinite detention in U.S. facilities—or deportation to El Salvador, which has agreed to accept them regardless of nationality. With Venezuela unable to issue passports, the U.S. has no legal pathway to return them home. El Salvador’s agreement effectively makes it the default destination, even though its prisons are overcrowded and lack basic human rights protections.

What led to the U.S. warning about China at the Panama Canal?

U.S. intelligence uncovered Chinese state-backed firms installing surveillance and logistics infrastructure near the canal’s Pacific entrance, including AI-powered tracking systems. The concern isn’t just economic—it’s strategic. If China gains access to real-time vessel data or scheduling control, it could disrupt U.S. naval mobility between oceans. The warning was a preemptive move to prevent a repeat of the Djibouti model, where China established its first overseas military base under the guise of commercial development.

Why is El Salvador willing to take American citizens?

Bukele’s government sees it as a bargaining chip. By offering to accept even U.S. nationals, he’s signaling absolute loyalty to Washington. In return, he’s secured over $400 million in U.S. security aid since 2023 and may now be positioning for billions more in infrastructure funding. For a country with a $26 billion GDP, this deal is economically vital—even if it means housing Americans in prisons designed for gang members.

What’s the legal status of deporting people to a country under a state of emergency?

Under U.S. and international law, deporting someone to a country where they face torture, arbitrary detention, or inhumane conditions violates the Convention Against Torture. Human rights lawyers argue that El Salvador’s state of emergency—where access to lawyers and due process are suspended—makes it legally unsafe. Yet the U.S. has repeatedly waived these obligations under the "safe third country" doctrine, setting a dangerous precedent for future administrations.

How does this impact U.S. credibility on human rights abroad?

The U.S. has long positioned itself as a global advocate for human rights. But partnering with a regime that has jailed over 83,000 people without trial, while ignoring prison conditions condemned by its own State Department, severely undermines that stance. Allies in Europe and Latin America are privately questioning whether the U.S. still upholds the values it claims to promote. The damage to soft power may outlast any short-term drop in border crossings.

What happens if El Salvador refuses to accept a deportee after agreeing?

The agreement lacks enforcement mechanisms. If El Salvador backs out, the U.S. has no legal recourse. The State Department’s internal documents acknowledge this, noting the deal is based on "political goodwill, not binding treaty obligations." That means the entire arrangement could collapse overnight if Bukele’s political calculus shifts—leaving thousands of deportees stranded in U.S. detention centers with nowhere to go.